What Does It Mean to Say That Gender Is Socially Constructed?

This page is a resources explaining general sociological concepts of sex activity and gender. The examples I comprehend are focused on experiences of otherness.

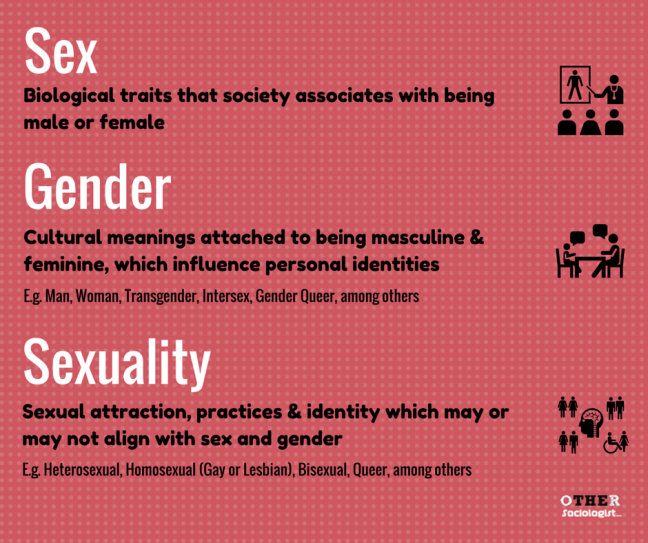

In sociology, we make a distinction betwixt sexual activity and gender. Sex are the biological traits that societies use to assign people into the category of either male or female person, whether information technology be through a focus on chromosomes, genitalia or some other concrete ascription. When people talk about the differences betwixt men and women they are oftentimes drawing on sex – on rigid ideas of biology – rather than gender, which is an understanding of how society shapes our understanding of those biological categories.

Gender is more fluid – it may or may not depend upon biological traits. More specifically, it is a concept that describes how societies decide and manage sexual activity categories; the cultural meanings fastened to men and women'south roles; and how individuals understand their identities including, but not limited to, beingness a man, adult female, transgender, intersex, gender queer and other gender positions. Gender involves social norms, attitudes and activities that society deems more appropriate for ane sex over another. Gender is besides determined past what an individual feels and does.

The sociology of gender examines how society influences our understandings and perception of differences between masculinity (what guild deems advisable behaviour for a "homo") and femininity(what society deems appropriate behaviour for a "woman"). We examine how this, in turn, influences identity and social practices. Nosotros pay special focus on the power relationships that follow from the establishedgender order in a given society, as well as how this changes over time.

Sexual activity and gender do non always marshal. Cis-gender describes people whose biological body they were born into matches their personal gender identity. This experience is distinct from being transgender, which is where one's biological sex does non align with their gender identity. Transgender people volition undergo a gender transition that may involve changing their dress and self-presentation (such as a name change). Transgender people may undergo hormone therapy to facilitate this process, simply not all transgender people will undertake surgery.Intersexuality describes variations on sexual activity definitions related to ambiguous genitalia, gonads, sexual activity organs, chromosomes or hormones. Transgender and intersexuality are gender categories, non sexualities. Transgender and intersexual people have varied sexual practices, attractions and identities as practice cis-gender people.

People tin can also be gender queer, past either drawing on several gender positions or otherwise non identifying with any specific gender (nonbinary); or they may movement across genders (gender fluid); or they may reject gender categories altogether (agender). The 3rd gender is oft used by social scientists to describe cultures that accept non-binary gender positions (run across the Two Spirit people beneath).

Sexuality is different over again; it is near sexual attraction, sexual practices and identity. Simply as sex and gender don't always align, neither does gender and sexuality. People tin identify along a wide spectrum of sexualities from heterosexual, to gay or lesbian, to bisexual, to queer, and so on. Asexuality is a term used when individuals do not feel sexual allure. Some asexual people might still form romantic relationships without sexual contact.

Regardless of sexual experience, sexual desire and behaviours can change over time, and sexual identities may or may not shift as a result.

Gender and sexuality are non just personal identities; they aresocial identities. They arise from our relationships to other people, and they depend upon social interaction and social recognition. As such, they influence how we understand ourselves in relation to others.

Gender

The definition of sex(the categories of man versus woman) as nosotros know them today comes from the advent of modernity. With the ascent of industrialisation came ameliorate technologies and faster modes of travel and advice. This assisted the rapid diffusion of ideas across the medical world.

Sexual practice roles describes the tasks and functions perceived to be ideally suited to masculinity versus femininity. Sex roles have converged across many (though non all) cultures due to colonial practices and also due to industrialisation.

For example, in early-2014, India legally recognised the hijra, the traditional third gender who had been previously accustomed prior to colonialism.

Sex roles were different prior to the industrial revolution, when men and women worked alongside i some other on farms, doing similar tasks. Entrenched gender inequality is a product of modernity. It'south non that inequality did not exist before, it's that inequality within the dwelling in relation to family unit life was not as pronounced.

In the 19th Century, biomedical science largely converged effectually Western European practices and ideas. Biological definitions of the trunk arose where they did not exist before, cartoon on Victorian values. The essentialist ideas that people attach to human being and adult female exist merely because of this cultural history. This includes the erroneous ideas that sex:

- Is pre-determined in the womb;

- Divers by anatomy which in turn determines sexual identity and desire;

- Differences are all connected to reproductive functions;

- Identities are immutable; and that

- Deviations from ascendant ideas of male/female must be "unnatural."

As I show farther below, at that place is more variation across cultures when information technology comes to what is considered "normal" for men and women, thus highlighting theethnocentric basis of sex categories. Ethnocentric ideas define and judge practices according to ane'southward own culture, rather than understanding cultural practices vary and should be viewed by local standards.

Social Construction of Gender

Gender, similar all social identities, is socially synthetic. Social constructionism is 1 of the key theories sociologists use to put gender into historical and cultural focus. Social constructionism is a social theory about how pregnant is created through social interaction – through the things we practise and say with other people. This theory shows that gender it is not a stock-still or innate fact, but instead information technology varies across time and identify.

Gender norms (the socially acceptable means of interim out gender) are learned from birth through childhood socialisation. We learn what is expected of our gender from what our parents teach us, as well as what we pick upward at schoolhouse, through religious or cultural teachings, in the media, and various other social institutions.

Gender experiences will evolve over a person'southward lifetime. Gender is therefore always in flux. We see this through generational and intergenerational changes within families, as social, legal and technological changes influence social values on gender. Australian sociologist, Professor Raewyn Connell, describes gender as a social structure – a higher guild category that society uses to organise itself:

Gender is the structure of social relations that centres on the reproductive loonshit, and the set of practices (governed by this construction) that bring reproductive distinctions between bodies into social processes. To put it informally, gender concerns the way man society deals with human bodies, and the many consequences of that "deal" in our personal lives and our collective fate.

Similar all social identities, gender identities are dialectical: they involve at least two sets of actors referenced against 1 another: "us" versus "them." In Western civilization, this means "masculine" versus "feminine." As such, gender is synthetic effectually notions of Otherness: the "masculine" is treated equally the default human experience by social norms, the law and other social institutions. Masculinities are rewarded over and to a higher place femininities.

Take for example the gender pay gap. Men in general are paid better than women; they enjoy more sexual and social freedom; and they accept other benefits that women do not past virtue of their gender. At that place are variations across race, class, sexuality, and according to inability and other socio-economical measures. See an example of pay disparity at the national level versus race and pay amongst Hollywood stars.

Masculinity

Professor Connell defines masculinity as a wide set of processes which include gender relations and gender practices between men and women and "the effects of these practices in bodily experience, personality and culture."Connell argues that culture dictates ways of being masculine and "unmasculine." She argues that at that place are several masculinities operating within whatsoever ane cultural context, and some of these masculinities are:

- hegemonic;

- subordinate;

- compliant; and

- marginalised.

In Western societies, gender ability is held by White, highly educated, middle-grade, able-bodied heterosexual men whose gender representshegemonic masculinity – the ideal to which other masculinities must collaborate with, accommodate to, and claiming. Hegemonic masculinity rests on tacit acceptance. It is not enforced through direct violence; instead, it exists every bit a cultural "script" that are familiar to us from our socialisation. The hegemonic ideal is exemplified in movies which venerate White heterosexual heroes, equally well as in sports, where physical prowess is given special cultural interest and authority.

A 2014 event between the Australian and New Zealand rugby teams shows that racism, culture, history and ability complicate how hegemonic masculinities play out and subsequently understood.

Masculinities are constructed in relation to existing social hierarchies relating to class, race, historic period and then on. Hegemonic masculinities rest upon social context, and so they reflect the social inequalities of the cultures they embody.

Similarly, counter-hegemonic masculinities signify a contest of ability betwixt different types of masculinities. Every bit Connell argues:

"The terms "masculine" and "feminine" point beyond categorical sex activity difference to the ways men differ amidst themselves, and women differ among themselves, in matters of gender."

Sociologist CJ Pascoe finds that young working-grade American boys police masculinity through jokes exemplified by the phrase, "Dude, you're a fag." Boys are called "fags" (derogative word for homosexual) non because they are gay, but when they engage in behaviour exterior the gender norm ("united nations-masculine"). This includes dancing; taking "likewise much" care with their appearance; existence too expressive with their emotions; or existence perceived as incompetent. Being gay was more acceptable than existence a man who did not fit with the hegemonic ideal – but being gay and "unmasculine" was completely unacceptable. One of the gay boys in Pascoe'due south report was bullied so much for his dancing and wearable (wearing "women'due south clothes") that he was eventually forced to drop out of schoolhouse. The schoolhouse's poor management of this incident is an unfortunately all-also-common example of how everyday policing of gender betwixt peers and inequality within institutions reinforce ane another.

Meet the video illustrating how hegemonic masculinity is damaging to men. Find that most of these ofttimes-heard sayings directed at boys and men utilize femininity and heterosexism as insults. (Heterosexism is the presumption that being a certain type of heterosexual person is "natural" and anything else is "not normal.")

Femininity

Professor Judith Lorber and Susan Farrell debate that the social constructionist perspective on gender explores the taken-for-granted assumptions about what it means to be "male person" and "female," "feminine" and "masculine." They explicate:

women and men are not automatically compared; rather, gender categories (female-male, feminine-masculine, girls-boys, women-men) are analysed to see how different social groups define them, and how they construct and maintain them in everyday life and in major social institutions, such equally the family and the economic system.

Femininity is constructed through patriarchal ideas. This means that femininity is always set up upwards every bit inferior to men. Every bit a upshot, women equally a group lack the same level of cultural power every bit men.

Women do accept bureau to resist patriarchal ethics. Women can actively challenge gender norms by refusing to let patriarchy define how they portray andreconstruct their femininity. This can exist done by rejecting cultural scripts. For example:

- Sexist and racist judgements about women's sexuality;

- Fighting rape culture and sexual harassment;

- By entering male-dominated fields, such as body-building or scientific discipline;

- Rejecting unachievable notions of romantic love disseminated in films and novels that turn women into passive subjects; and

- Past generally questioning gender norms, such as by speaking out on sexism. Sexist comments are one of the everyday ways in which people police and maintain the existing gender club.

Every bit women exercise non have cultural power, there is no version of hegemonic femininity to rival hegemonic masculinity. There are, however, dominant ideals of doing femininity, which favour White, heterosexual, middle-grade cis-women who are able-bodied. Minority women exercise non savour the aforementioned social privileges in comparison.

The popular idea that women do non get ahead considering they lack confidence ignores the intersections of inequality. Women are at present beingness told that they should simply "lean in" and enquire for more help at work and at abode. "Leaning in" is a limited style of overcoming gender inequality only if you're a White woman already thriving in the corporate globe, by plumbing fixtures in with the existing gender order. Women who desire to challenge this masculine logic, even by asking for a pay ascension, are impeded from reaching their potential. Indigenous and other women of colour are fifty-fifty more disadvantaged.

https://plus.google.com/110211166837239446186/posts/7Ujcek5Auov

Some White, middle-grade, heterosexual cis-women may exist better positioned to "lean in," but minority women with less power are non. They're fighting sexism and racism and grade discrimination all at once.

Cross-national studies prove that social policy plays a pregnant office in minimising gender inequality, especially where publicly funded childcare frees up women to fully participate in paid work. Cultural variations of gender across fourth dimension and place as well demonstrate that gender change is possible.

Transgender and Intersex Australians

Nationally representative figures drawing on random samples do not exist for transgender people in Commonwealth of australia. The Sexual activity in Commonwealth of australia Report organised a sub-set of questions to address transgender or intersex issues, merely these were not used as no ane in their survey specified that they were part of these groups. The researchers recollect that transgender and intersex Australians either nominated themselves broadly as woman or men, and as either heterosexual, gay, lesbian, bisexual or asexual. Alternatively, transgender and intersex Australians may have declined to participate in the survey. The researchers note that around ane in i,000 Australians are transgender or intersex. The Private Lives written report, which surveyed over 3,800 lesbian, gay, transgender, queer, intersex and asexual (LGBTQIA) Australians finds that 4.four% identify as transgender (and a further 3% prefer some other term to describe their sex activity/gender other than male person, female person or transgender).

American and British estimates are no more exact. Smaller or specialised surveys on issues such as surveillance and tobacco judge that between 0.2% and 0.five% of Americans are transgender, while surveys in the United kingdom of great britain and northern ireland identify that upwards to 0.1% of the population has began or undergone gender transition (noting this does not capture other people who may exist considering transgender options).

The research shows that transgender people face various gender inequalities. They lack access to adequate healthcare; they are at a loftier risk of experiencing mental disease as a result of family unit rejection, bullying and social exclusion; and they face high rates of sexual harassment. They too face much discrimination from doctors, constabulary, and other authority groups. Work colleagues discriminate against transgender people through breezy channels, past telling them how to apparel and how to act. Employers discriminate in tacit ways, which might manifest as gender bias leading managers to question how gender transition may bear on on work productivity. Employers also discriminate in overt ways, by promoting and affirming transgender men only when they conform to hegemonic masculinity ideals, and more often than not property back or otherwise punishing transgender women. Feminism has all the same to fully embrace transgender inclusion as a feminist crusade. Transgender advancement groups have made great strides to increment visibility and rights of transgender people. All the same, mainstream feminism's reticence to accept up transgender issues serves only to perpetuate gender inequality.

Transgender people have always lived in Australia. Read beneath to larn more most sistergirls, Ancient transgender women, and how Christianity attempted to displace their cultural belonging and femininity.

Intersex people take been, up until recently, heavily defined in pop culture by largely damaging ideas from medical scientific discipline. Practitioners tend to nowadays intersex conditions through a pathological lens, oft leaving individuals and families feeling that they have little choice other than surgical intervention to "correct" gender. Sharon Preves's research shows that medical interventions ofttimes accept devastating effects on gender identity and sometimes on sexual function. Girls with an enlarged clitoris and boys with a micro-penis are judged by doctors to have an ambiguous sexual practice and might be operated on early in life. What is meant to be a cosmetic fix to make bodies "normal" can sometimes lead to harmful self-dubiety and relationship problems for some intersex people. Others exercise not experience such trauma, and they feel more supported especially when parents and families are more open to discussing intersexuality rather than hiding the condition. Much similar transgender people, intersex people have likewise been largely ignored by mainstream feminism, which only amplifies their feel of gender inequality.

Gender Beyond Time and Identify

Behaviours that come to be understood as masculine and feminine vary across cultures and they change over time. As such, the way in which we understand gender here and now in the city of Melbourne, Australia, is slightly different to the way in which gender is judged in other parts of Australia, such as in rural Victoria, or in Indigenous cultures in remote regions of Australia, or in Lima, Peru, or Victorian era England, and then on. Still, the notion of difference, of otherness, is central to the social arrangement of gender. As Judith Lorber and Susan Farrell argue:

"What stays constant is that women and men accept to exist distinguishable" (my accent).

Gender does not look then familiar when we expect at other cultures – including our own cultures, back in fourth dimension. Here are examples where hegemonic masculinity (problems of gender and power) look very dissimilar to what nosotros've get accustomed to in Western nations. Permit's start with a historical example from Western civilization.

16th Century Europe

European nations have not always adhered to the same ideas about feminine and masculine. As I noted a few years ago, aloof men in Europe in the 16th and 17th Centuries wore elaborate high-heeled shoes to demonstrate their wealth. The shoes were impractical and hard to walk in, just they were both a status symbol as well equally a sign of masculinity and power. In Western cultures, women did non begin wearing loftier-heeled shoes until the mid-19th Century. Their introduction was not about social status or power, but rather it was a symptom of the increasing sexualisation of women with the introduction of cameras.

The cultural variability of how people "exercise gender" in different parts of the earth demonstrates the cultural specificity of gender norms. Gender has unlike norms at different places at unlike points in time. The Wodaabe nomads from Niger are a example in bespeak.

Wodaabe (Niger)

Wodaabe men will wearing apparel up during a special ceremony in gild to attract a wife. They wear brand-up to show off their features; they wearable their best outfits, adorned with jewellery; and they bare their teeth and dance before the unmarried women in their village. To the Western center, these men may appear feminine, as Western civilisation assembly make upwards and ornamental trunk routines with women. Withal in this pastoral civilization, the men's elaborate make-upwards, wearing apparel and behaviour are a show of virility. The women choice the men according to their costume and dance. This is some other custom that is contrary to dominant models of gender in the West, which demand that women be more passive, and wait until a man approaches her for romantic or sexual attention.

In that location are various other examples of cultures and religions where gender is done in culling means which recognise genders across the binary of male/female person.

"Two Spirit" (Navajo Native American)

I wrote about the "2 Spirit" People found among the Navajo Native American cultures, who make upward ii additional genders: the feminine human (nádleehí) and masculine woman (dilbaa). They are traditionally considered to be sacred beings embodying both the feminine and masculine traits of all their ancestors and nature. They are chosen by their community to represent this tradition, and one time this happens, they live out their lives in the opposite gender, and can also get married (to someone of the opposite gender to their adopted gender). These couples accept sex together and they may also have sex with other partners of the opposite gender. If they accept children, they are accustomed into the Two Spirit household without social stigma.

Female Husbands (Various African Cultures)

Over 30 cultures in African regions permit women to marry other women; they are called "female husbands." Typically they must already exist married to a man, and they are almost exclusively wealthy as they demand to pay a "helpmate-price" (equally practice men who marry women). The women do not have sexual relations, information technology is more of a family and economic arrangement. (Homo rights activists claiming this maxim that because homosexuality is shrouded in secrecy, these women may non want to admit to sexual relationships; withal, there is no empirical testify to this effect.)

The Nandi people of Kenya allow this tradition. It is permissible when an older woman has not borne a son, and she will marry a woman to bear her a male heir. The "female husband" will now come across herself equally a man, and will abscond from feminine duties, such as carrying objects on her head, cooking and cleaning. The female person husband takes on male roles, such equally entertaining guests while her wife waits on them. The Abagusii people of Western Kenya allow a female husband to take a wife to bear her children, and the biological father has no rights over them. The Lovedu of South Africa and the Igbo of Benin and Nigeria also exercise a variation of female married man, where an independently wealthy woman will proceed to be a wife to her male person husband, but she will fix a separate dwelling house for her married woman, who will acquit her children. These arrangements go on in the present-day and can be platonic for young unmarried mothers who need security.

Among the Igbo Land in Southeast Nigeria, both women will continue to have sexual relations with men, withal, the female person husbands must exercise this discreetly. If she becomes pregnant, her children are considered "illegitimate" and are treated every bit outcasts. The children of her wife remain her responsibility and they are not shunned. The female-husband tradition preserves patriarchal structure; without an heir, women cannot inherit land or property from their family, but if her wife bears a son, the female wife is immune to carry on the family name and pass on inheritance to her sons. Nigerian historian, Dr Kenneth Chukwuemeka Nwoko calls this arrangement a patri-matriarchy. The female husband would be left without status if she fails to produce a male heir, yet once assuming their role as hubby, she receives authorisation over her family.

Kathoey (Thailand)

The Kathoey from Thailand are born biologically male but effectually half place equally women while the balance identify every bit "sao praphet vocal" ("a second kind of woman"). Alternatively, they see themselves every bit transgender women; and others still see themselves every bit a "tertiary sexual activity." Monarchy rule and resistance to external colonialism led to an aggressive modernisation campaign that made traditional Kathoey gender practices more difficult. While Thailand generally has less punitive laws about homosexuality (it is not illegal to be gay), LGBTQIA people do not accept the same rights as heterosexual couples, and the Kathoey struggle for social recognition of their gender identity.

Kathoey (Ladyboys) – Documentary from faithjuliana on Vimeo.

While the Kathoey are tied to older gender traditions, Peter Jackson, Professor of Thai civilization and history at the Australian National University, argues that present-twenty-four hour period identities and activism amongst Kathoey are informed by both modernistic and global sensibilities that arose after Globe War II. Kathoey women have become a large tourism attraction which stands at odd with their own legal struggles as well as those of other LGBTQIA people in Thailand. Jackson writes:

"My inquiry on Thai queer genders and sexualities reveals that contemporary patterns of kathoey transgenderism are just as contempo and as different from premodern forms as Thai gay sexualities, with Thailand's kathoey cultures taking their current forms as a upshot of a 20th century revolution in Thai gender norms… The cultural prominence of gender in Thailand is reflected in the intense popular fascination with the transgender kathoey and the relative invisibility of Thailand's large population of gender-normative gay men in both local and international media representations of queer Thailand."

Glory Kathoey, Nok, is fighting for legal and medical support of poor and rural transgender women in Thailand. She has a Masters degree and is a successful business adult female. She feels lucky to have e'er had her family's support, but that did not end her from being jailed as a youth for conveying fake female person identification. She now runs a charity helping underprivileged transgender women gain access to medical treatment to back up their gender transition. She is also seeking to challenge the police force to recognise transgender people'due south gender identity, as official documentation currently forces them to legally identify equally their biological sex.

From the Documentary Ladyboys, Episode, "Celebrity Ladyboys."

Studying Gender Sociologically

We tin can written report how people "do" gender using ethnographic methods, such as fieldwork and observation. If nosotros are interested in understanding how people make sense of their identities, or we want to get in-depth into their gender experiences, we would apply other theories or methods, such as qualitative methods, like one-on-one interviews. If we wanted to study direct measures of gender inequality, we might apply quantitative methods such as population surveys to cross-reference how people from different genders are paid at work; or we might get people to deport out time-use diaries to collect information about how much housework they exercise or how much time they spend doing tasks at work relative to their colleagues; and so on.

Mixed methods can exist ideal when studying gender inequality. For example, in domestic labour within families, in order to "get beneath the cover story" of domestic equality and domestic labour. This might involve carrying out time use diaries in add-on to interviews, or conducting extended interviews with each member of the family to get a holistic moving-picture show of how their gender identities, gender practices and family "cover story" diverge.

Learn More

Read more of my enquiry on gender and sexuality.

- Folklore of Sexuality

- 'That's My Australian Side': The Ethnicity, Gender and Sexuality of Immature Women of S and Central American Origin,Journal of Folklore 39(ane): 81-98.

- 'A Woman Is Precious": Constructions of Islamic Sexuality and Femininity of Turkish-Australian Women', in P. Corrigan, et al. (Eds)New Times, New Worlds, New Ideas: Sociology Today and Tomorrow. Armidale: The Australian Sociological Association and the University of New England.

- My blog posts on Gender & Sexuality

- My blog posts on Gender at Work (on Social Scientific discipline Insights)

- Follow me on Facebook for short-form give-and-take of gender and sexuality in the news and pop culture, as well as other issues of intersectionality.

- Circumvolve me on Google+ to get micro-weblog posts on gender, intersectionality and otherness.

- Get further analysis and resource from my Pinterest board: Sociology of Gender and Sexuality on Pinterest.

Citation

To cite this commodity:

Zevallos, Z. (2014) 'Sociology of Gender,' The Other Sociologist, 28 Nov. Online resource: https://othersociologist.com/sociology-of-gender/

Note: This page is a living document, meaning that I volition add to it over time.

Source: https://othersociologist.com/sociology-of-gender/

0 Response to "What Does It Mean to Say That Gender Is Socially Constructed?"

Post a Comment